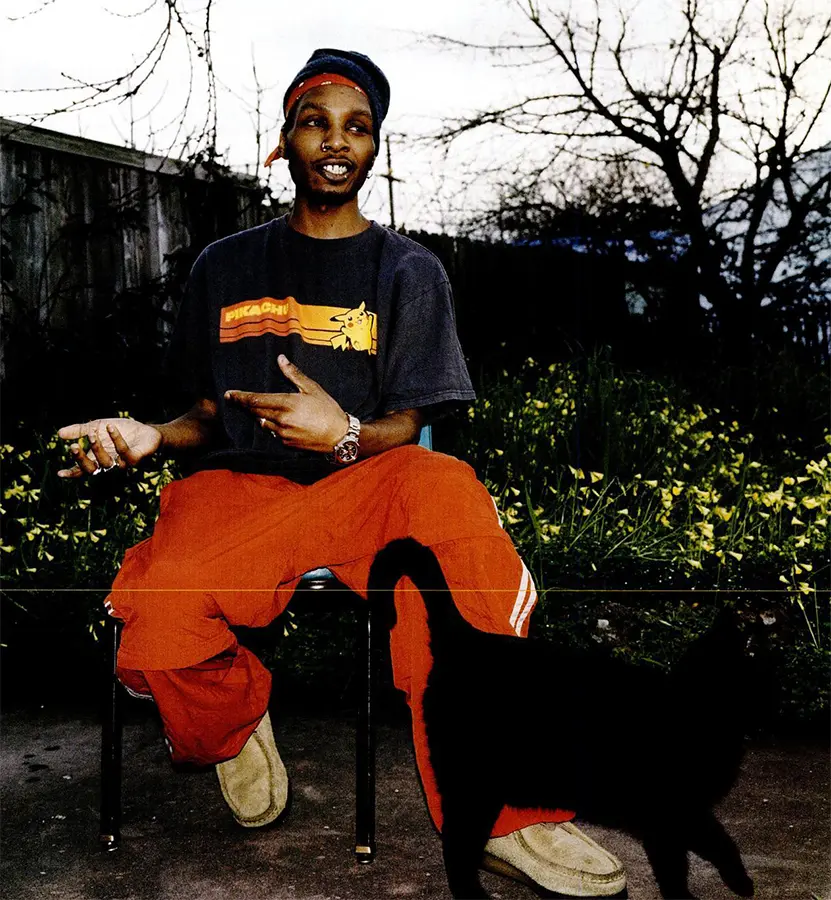

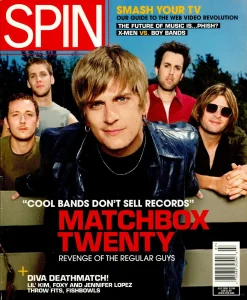

Originally published in SPIN

July 2000

Pages 134-137

Written by Charles Aaron III

Photographs by Jeff Minton

Ultra-magnetic poetry: Del’s next LP takes shape.

GLOSSARY

Del the Funky Homosapien has always been known for his ever-evolving slangy vocalese—part street-corner ball-buster, part gaslit snowboarder. Here’s a brief rundown:

Boze (adj.): flat-out wack

Clean (adj.): in reference to quality hip-hop song, album beat, etc.

Driggity (adj.): drunk

Duzzled (adj.): cluelessly puzzled

Fragglicious or Vigglicious (adj.): very pleasing

Freakers or Juicers (adj. orn.) 1: extremely noteworthy 2: extremely noteworthy individual(s) or acts)

Rippers or Ultra Rippers (adj. or n.): high level of skill, or individual(s) with same Yiggity (interj.): variation of YO!

The bell rings, and there’s a rustling in the little yellow house.

“Just a minute, aa-ight?”

It’s late on a wet-sock-gray, Bay Area afternoon. Inside, the rapper known as Del the Funky Homosapien glides down a dark hallway, cigarette drooping off a pierced lip, green do-rag atop his head, broom in hand. He begins sweeping in a balletic whir, quick whisks in all directions. A mix tape clicks on, and Del rhymes along, his cadence growing bouncier, as if he’s flexing vocal calisthenics. Riding Jay-Z’s bumptious “It’s Hot (Some Like It Hot),” sweeping to the beat, he could be every kid at minimum-wage closing time. Intended or not, it’s a fabulous anti-star turn.

Ever since his P-Funky 1991 debut, I Wish My Brother George Was Here, on Elektra, Teren Delvon Jones has been hip-hop’s most winsome enigma.

The teenage cousin of gangsta rap librettist Ice Cube, he showed a charisma that caught even the most blasé folks staring. But like De La Soul orphaned in Cali, Del shied from the shoot-’em-up spotlight (“I dis the facial value of your ballyhoo,” he mused on his first album).

Throughout the ’90s, he kept a low and cryptic profile, said to be fighting substance abuse and financial woes. But with his first proper album in seven years—Both Sides of the Brain, on Hiero Imperium (a label he co-owns with buds Souls of Mischief, Casual, et al.)—Del, 27, returns as an outsider unscarred by the game, lobbing gleeful spitballs at the hip-hop “shoo-be-doo-be.” Deemed too “obscure” by commercial rap handbook The Source, the album debuted, shockingly, at No. 118 on the pop charts.

“He just totally does what he fucking feels,” says Dante Ross, the Elektra A&R VP (and now Everlast producer) who first signed him in 1990 and remains a close friend. “Del’s like the antithesis of the jiggy aesthetic. But as far as skills, he’s up there with anybody.”

Post sweep-up, Del reemerges in a natty sweater and baggy cargoes. With a sideways grin, he shows me into his cram-jammed rec room/studio, where Both Sides was recorded. Puttering cagily amid an endless array of CDs, vinyl, videogames, anime posters, and stacked books (from music theory to African history to Wiccan magick), he sizes me up, questions my questions, lights incense. Before long, the thought-bubbles start popping.

On major labels: “If a kid gets signed, like I did, he thinks, ‘They signed me; they must want me!’ Of course, they don’t even know you; they only know who they want you to be. The ill thing is, before long, that’s who you are! It’s like, they don’t change your music, but you’re so scared of failing, you change it yourself.”

Blazing up an Indian bidi cigarette and balancing a plate of veggie burgers on his SP1200 drum sampler, he speaks to rumors that have dogged him since he bitterly departed Elektra in ’95. “People be duzzled [see glossary], thinking l’m some hippie-ass nigga on drugs. But to tell the truth, I’ve always been bugged out. I was born hella hyper, dude. I gotta be goofy sometimes to just, you know, please myself…. I’m supposed to be some intellectual weirdo, but basically, I’m just a fool from Oakland. Yiggity.”

Del’s now-you-know me, now-you-don’t persona has become his defining punch line. Even on his debut, mentor Ice Cube asked, “Del, what the fuck is a funky homosapien?” To which Del replied, “It’s a human being, fool. A funky human being.” But the Compton gangsta-rap don never quite comprehended his cuz from Oakland Hills. Cube and producer DJ Pooh’s conception of Del as a starchild stepson of Parliament Funkadelic (à la Digital Underground) was fresh-off-the-shelf entertainment (see oddball hit “Mistadobalina”), but it was more than a little affected.

“Cube loves money, while Del was this kid with two nose piercings who was on some other shit,” Ross says. “Del felt like an actor playing a role in Cube’s little movie just to sell records. Then when the album didn’t sell as well as it should’ve [about 300,000 copies], everybody at Elektra, and Cube, stopped paying attention to him.”

Feuding with Cube, fighting with an ex-girlfriend, Del tried producing 1993’s gritty, lyric-lickin’ follow-up, No Need for Alarm. Heads were wowed by his MC chops, but the songs were patchy, and Del became isolated, experimenting with psychedelics and drinking heavily. His “gentle nature” kept Ross on his side, but other bosses were less forgiving. After a ludicrous suggested pairing with Kris Kross producer Jermaine Dupri, a third album, perhaps Del’s finest, was rejected (Future Development, available at www.hieroglyphics.com, featuring the brilliant major-label indictment “Del’s Nightmare”). Elektra coldly terminated the relationship via registered letter.

But with Both Sides’ lo-fi synth twurk, the funky human being reasserts his brash, still-frisky voice: “Flamboyant, flamin’ fools like mesquite / Let’s eat!” In critic-speak, Del hotwires Slick Rick’s narrative cheek with Q-Tip’s abstract poetics, and Kool Keith’s audacious wit-but even that doesn’t quite get it. Del isn’t a flossy, look-at-me! ego but a giddy, look-at-that! superego. He’s the dusky-voiced, bright-eyed cynic scribbling notes on the city bus. His idea of a fantasy superhero is a cackling crack fiend who uses a Garfield beach towel for a cape. He disses a rival as a “lactose-intolerant lummox.” No conscious martyr decrying thug life, Del’s just a hyper-articulate guy who wants thugs to leave him be.

“He’s not trying to make a big spectacle of himself, and that sorta confuses people,” says veteran Bay Area producer Dan “The Automator” Nakamura, who’s collaborating with Del on 30/30, a Dr. Octagon-like “supergroup” with DJ Kid Koala. “These days, rappers are supposed to be having champagne orgies in limos. Meanwhile, Del’s walking around talking to people about the last ten books he just read.”

He’s walking, or riding the bus, because he lacks a license and hates asking for rides. After our interview, I’m designated driver for a show in San Jose (the car of Hieroglyphics manager/label boss/producer Domino is on the fritz). It’s a dreary, rainy night, but a support group forms-DJ Jay Biz, Pep Love, Phesto, Automator, Domino. I hoist a duffel bag of tapes, CDs, and T-shirts into the trunk. Welcome to the Hiero road show.

Back in the early ’90s, the Hieroglyphics crew gathered around Del at Oakland’s Skyline High School. Souls of Mischief (A-Plus, Opio, Phesto, and Tajai) clocked a hit for Jive with ‘93 Til Infinity; Casual and Extra Prolific came next with Jive solo deals. For a minute, the Hiero logo-a round, three-eyed face with flat-line mouth, drawn by Del-was stickered nationwide. Amid the era’s pitched rebellion, it was a sign of talented black kids who wouldn’t be reduced to gangstas or goody-goodies.

But by the mid-’90s, Hiero’s fortunes waned, and the MCs were soon rocking day jobs to subsist (Del, most publicly, at Leopold’s record store in Berkeley). At the urging of Domino, a.k.a. Damian Siguenza, 29, a onetime fan from San Francisco’s Mission District, they reorganized-setting up a website, hawking merch, playing live, incorporating. The ’98 Hieroglyphics posse album Third Eye Vision has sold 80,000 copies, and Del’s latest—with new distribution in place—should earn him far more than Elektra ever paid. Hiero Inc. now occupies a warehouse space in industrial West Oakland, where Domino and Souls member Tajai Massey handle business.

Hieroglyphics’ ability to sustain one another has family roots. Most members were supported by two, often artistically inclined, parents. Domino’s Salvadoran dad played bass for new wave R&B combo Mink DeVille. Del’s father, Delma, was a visual artist; his mom, a college-degreed police-department employee, stressed academics. “I was reading a lot at an early age,” he says, “and Dad always kept me up on shit, as far as our African heritage.” When his parents’ marriage split, Del admittedly “got stupid” (he was kicked out of two junior highs), and his younger brother, Tyson, got into “some gangster bullshit” (he’s now serving jail time). But the family hung in-“Moms got me my first SP1200.” Hip-hop, once a hobby, became a guiding passion.

From the start, Del stood out. And not just because his cousin was down with N.W.A. “I met Del in kindergarten,” says Casual (a.k.a. John Owens), 25.

“He wanted to borrow this Atari game called Yars Revenge, and to this day, I remember immediately thinking, ‘Dang, this cat’s mind is going someplace else.'” Adds Ross: “Del doesn’t have a filter between what he feels and what he says. He speaks from his heart to everyone all the time.”

I get a dose of unfiltered Del just as we’re leaving his house (in Richmond, just north of Oakland) for the evening’s gig. Domino asks whether Del’s girlfriend, Sabrina (a beautiful, dreadlocked UC Berkeley student with whom he’s lived for two years), is going. “Naw,” he snaps, with a weary edge of self-loathing. “She’s seen that shit before; I know I have.” As he stalls, brooding, I ask about his study of Japanese, which he’s taught himself to read and speak. Puffing a bidi, Del shakes his head. “Man,” he says, his voice almost childlike, “I got so much left to learn about everything.”

On the interstate south, Del sounds off on how Q-Tip has been unfairly abandoned by his fans (“Motherfuckers be saying he betrayed them. That’s boze, dude!”). We get to the venue late, and Del quickly downs a couple of drinks before hitting the stage. Smirking and working like a smooth pro, he sprinkles in a few old faves-“Dr. Bombay,” “Boo Boo Heads.” Then, suddenly, he starts testing the suburban, collegiate “back-pack” crowd (a core of Del’s fan base) on whether they really care about hip-hop, or whether it’s just a phase they’re going through. It’d be pretty cutting, if he weren’t so tipsy. Actually, it’s still pretty cutting.

As we sit in the car afterward, Del waits for a nice chunk of bills for 40 minutes of what he glibly describes as “slippin’ and slidin’.” Despite his undeniable star qualities (fans range from Lauryn Hill to Eminem), and a clear desire to sell more records, he seems just fine reclinin’ here in a San Jose parking garage, unnoticed.

“He’s a true outcast, even among his friends,” Domino says. “I think if he ever did get famous, he’d be miserable. He needs to do his regular Del stuff, like catch the bus to the office, pick up his check, walk to the bank, deposit his check. He doesn’t see himself as anyone extra-special. And I think that’s why people believe in him so deeply.”

Reproduced on Hieroglyphics.org for educational purposes.