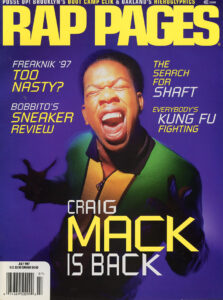

Oakland’s Hieroglyphics Crew Regroup to Relaunch

Originally published in: Rap Pages

July 1997

Pages 50-53, 92

Story by Jazzbo

Photos by Carla Cummings

Perennial Westside MC Ice Cube created the Hieroglyphics. Actually, it was Del the Funky Homosapien, who, at 17 years of age, got a record deal on the strength of being Ice Cube’s cousin. Del, in kind, hooked up his boys Souls of Mischief—Opio, Tajai, A-Plus and Phesto—and Casual, and they launched the Hieroglyphics crew. This story Is running through my head as Opio, A-Plus, Pep Love, manager and producer Domino and I settle into a table at a grill on Telegraph Avenue in strangely functional Berkeley, California.

Before embarking on my journey to meet the members of the nine-plus East Bay Area crew, a point was made to retrieve my old Hieroglyphics demo tapes from my dubbing-syndicate stash. Damn, I wish my boy Jason were here. He’d have the real tape I wanted—the one with “Cab Fare,” the Taxi-laced song that flipped the Bob James TV show theme. Fear of a Black sample inhibited the song from ever being issued on Souls of Mischief’s ‘93 til Infinity, yet somehow it became as legendary as one can become without ever having been released. Is “legendary” better than a “classic”?

Ah…Hiero tapes. They’re like currency in some parts of the world. Better, even. Dead presidents never kept someone company on headphones while making midnight treks to the library. Dubs of dubs of dubs—to the point where you hear more white hiss than Black beat—still make the journeys from East Bay apartment bedroom to North Carolina dubbing deck to a walkman in London on through to the speakers of a New York record store and back to the Bay Area again.

After spotting A-Plus waiting on Telegraph Ave., a gangly, white skater approached him, a pedestrian in awe of his idol. Minutes later, a group of city-slick Japanese kids were overcome with the same beholden veneration. They exchanged pounds with the ever-courteous MC and were on their way, giddy with excitement.

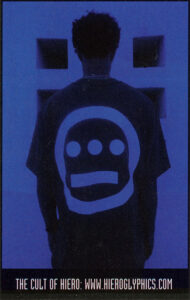

It’s amazing how this Hip-Hop coterie are rhapsodized worldwide. Even now, after being out of the public eye for so long, you could travel to any place on the globe—Bosnia, for example—and, guaranteed, there’s a pocket of Hieroglyphic heads huddled in some abandoned schoolhouse reciting lines like, “I find it fun to smash MCs into fine bits…” These heads heed the songs as if they were biblical lessons in a God-fearing world. The lyrics become the scriptures, the beats are the hymns. Their story recorded through lost tapes and demo dubs in neverending perpetuity. It’s the cult of Hieroglyphics.

The history of the Hieroglyphics continues to fill my cerebral cortex. Del had signed his contract and was in preparations for his debut, I Wish My Brother George Was Here, while he was still a senior In high school (1990). Until then, Hiero was just a loose collection of friends from school that included the guys in Souls of Mischief, Casual and some others. Domino, the crew’s manager, didn’t meet Del until later in the year. He had been living in a small side room in the back of San Francisco’s famed record haven, Groove Merchant (a beatmaker’s dream, no?), when he met frequent shopper Dante Ross, Del’s A&R [Elektra Records] representative. Introductions were made, and everyone hit it off. A short time later, Extra Prolific, Pep Love and Jay Biz all entered the fold. The pieces were complete.

From that point forward, the story is well-known. Each group or artist released an album (except Pep Love and Jay Biz), some achieving modest success. Recently, however, adversity has infiltrated the camp. Del was dropped from his label just after completing, but not releasing, his third album for Elektra, Future Development. Once regarded as the saviors of West Coast Hip-Hop, Souls of Mischief were dropped from Jive Records after No Man’s Land, the little-heard follow-up to their auspicious debut. Casual, too, was dropped from Jive after not living up to the label’s expectations with Fear Itself. And Extra Prolific completed the Jive trifecta when he was released weeks after his album came out.

You would think that living in your hometown after being dropped would be a blow to the ego, a stinging feeling local basketball heroes must feel after being cut by the NBA. But today there is a different demeanor demonstrated by the four. They seem relaxed, more confident. Almost rejuvenated. Some questions are certainly in order because they look too at ease for a crew that has suffered the humiliation of rejection from the recording industry.

“We’re free,” Domino says simply, with a bit of a smile. At Hieroglyphics Central, there’s a new mode of operation: independence. After being considered disposable, Souls of Mischief, Del, Casual, and Pep Love and Jay Biz regrouped in true Voltron fashion to form their own label. They’re also making final preparations for the release of Third Eye Vision, the long-awaited Hieroglyphics Family Album set for release in July. It’ll mark the first time, outside of late-night rhyme sessions and your basic fooling around, that the crew will record together as one solid unit.

“It’s an idea we’ve always had,” Domino explains. “After the situations with Del, Souls and Casual, we felt that this would be the best way to come back out to the public.”

Certainly, fans have cherished moments like “Burnt,” “No More Worries” and “Batting Practice,” songs that created new configurations out of the Hieroglyphics MCs. Those songs always spawned the questions of “What if…?” What if they did a song with just Del and Casual? What if it were Opio and Del? Third Eye Vision was made to answer the What ifs.

“Basically, the Hiero album isn’t any different than what we’ve been doing. Yes, it’s a little different working with the other members of Hiero, but it’s a natural situation,” says A-Plus. “Before Souls were even out, it was stuff we were doing anyway. Even just on the side or whatever, we’ve rhymed with each other.”

The fan support is still there. Any doubt was removed when 1,000-plus fans showed up for their “homecoming” show at San Francisco’s Maritime Hall in March, with many fans lining up as early as 2 p.m. to get in. At Unity in LA at the end of April, nearly 3,000 fans showed up. Not bad for being out of the Hip-Hop spotlight for a couple of years.

The crew has certainly been tested and regrouping and emerging as a unified force is certainly to their advantage. “We’re relying on each other to be a strong-ass unit,” Opio concurs. That strength in numbers will give the Hieroglyphics momentum coming into the

industry again. Because what will be most challenging will be the business of independence. Reduced barriers to entry into the record industry means just about anybody can make a record and form a label. More players, of course, means more competition—for profits, press, radio time, etc.—and inevitably, also means a smaller piece of the pie for everyone involved.

“I don’t think we could come out independently, successfully, if we hadn’t been out before,” Domino says. “The things that we’ve established, the relationships with the fans, the DJs, the press, it’s almost impossible to crack those doors nowadays. We have those ins. Those are the type of opportunities we have that other independents don’t have.”

But where did it go wrong in the first place? Jive and the Hieroglyphics had a tense relationship, aggravated by the fact that a large portion of the Hiero eggs were in one Jive basket. Right after the release of Souls of Mischief’s ‘93 til Infinity, it was clear that the two sides had different goals, says Domino. “Our main thing was that we wanted to have longevity in the industry, like a Gang Starr or Tribe [Called Quest]. Maybe sell some units, but to also build a career.”

Adds A-Plus: “That’s what they said they would do, but that wasn’t how it turned out.”

Two events can be pinpointed as flashpoints for the ultimate divorce. One was Extra Prolific’s profanity-laced, alcohol-induced tirade against Jive executives at the release party for the Low Down Dirty Shame soundtrack in the summer of ‘94 (Extra Prolific was swiftly dropped from the label in less than 12 hours). It’s no coincidence that Extra Prolific is no longer in the Hieroglyphics. Aside from driving a permanent wedge between the crew and Jive Records, he also clashed with the crew’s members and, they say, was never around when it came time to handle business as a unit. Did anybody else wonder why he was in the crew to begin with? His rather mediocre style and mundane creations never really was in sync with the artistic output of the rest of Hiero. “I don’t want to run foul,” says Casual now, “but he’s faulty.”

The second event was No Man’s Land, the sophomore album from Souls of Mischief. That album can be regarded as just short of a disaster for the group. Given their progressive nature, No Man’s Land was a huge disappointment, a contrived attempt to avoid making “95 Til Infinity” rather than a natural progression of talent and ideas. While in interviews, the group justified their position and said all the right things—we wanted to focus on the bump, we’re real happy with this album, etcetera—it was clear their hearts weren’t into it.

“That album is a strange creation,” admits A-Plus. “It was made under the most stressful situations that we were under to date. Speaking for myself, I wasn’t hella focused on the album. I wasn’t happy with the album, I wasn’t happy with a whole lot of stuff at that point in time. I wasn’t even trippin’ off making a record, really.”

The consensus is that there was no focus. Too many problems with the record company, they say. But most groups blame their record company for the most trivial things, using it as a crutch to explain their lack of success. To a certain extent, the same holds true for the Hieroglyphics. But they also have a legitimate gripe. The day No Man’s Land was released, relations with Jive had reached a breaking point and Domino was informed that effective immediately, Souls and Casual would be dropped (though the official announcement wouldn’t be made until later). No more money, no more promotion, no more support. They were dropped, and even worse, made to look the fool for selling only 30,000 – 40,000 records.

“They were frustrated with us, we were frustrated with them, Opio asserts. He follows with a long tirade against his former label, ending with an emphatic, but simple statement: “Fuck record companies.”

For Pep Love, the dissolution of his cronies’ relationships would appear to have set him back even further in his quest to make it in the Hip-Hop game. “Actually, when I saw all the things they were going through, all the drama they had, I felt blessed. I didn’t have to go through it, but I still got to see what was involved.” Pep is heavily featured on the Family Album on songs like “You Never Knew” (with everyone in Hiero), “See Delight” (with Opio) and “After Dark” (solo). “This whole thing is a blessing. I don’t think we would even be doing a Hiero family album if none of this happened.”

Domino admits that until last year, when the idea for the group’s label, Hieroglyphics Imperium, was conceived, the crew rarely hung out together. Now, he says, you can really feel the family vibe.

“In hindsight, you can say it’s a positive thing,” he adds. “Sure, any time someone says they don’t want you, it’s hard, at least for me, to have it not bring you down at least a little bit. I think the main thing it did was cause everybody to take inventory of themselves. Everyone realized this industry isn’t as easy as they first thought. There were a lot of things we didn’t do correctly in the situation. The bad times made everyone take a step back and reflect on themselves, what mistakes we made and how we can approach it better.”

It’s late March in Oakland at Tajai’s house near the lake [Lake Merritt]. To date, 30 songs have been recorded for the Hiero Family Album. Song selection and distribution remain the only major question marks, though Domino insists that a deal with a major distributor is imminent.

Tajai’s house is spacious inside, but sparse with furniture. His picture from the Senior Prom, as well as photos from his youth, reside inside a cabinet on the dining room wall. Opio and Domino are milling about the house, a couple of local friends watch videos, and Tajai sits at the table working on a laptop. Phesto is nowhere to be found. “He’s alone with us,” Domino says in trying to explain his conspicuous absence over the last few weeks. “He’s very to himself.”

Behind Tajai is Del, playing video games imported from Japan, making sound effects for his quick punches and roundhouse kicks. BDP’s Edutainment blasts through the house.

Speaking of the Blastmaster, consider this moment at the recent Gavin music industry convention in New Orleans last February: Hiero are on the local radio station doing what they do so well—freestyling. KRS-One, in town as well, hears them on the radio and directs his man to drive them down to the station. KRS bursts onto the scene, grabs A-Plus by the shoulders and says into his face, “Finally! Finally! Finally! You’re free! I’m still chained, but you’re free!”

The cult of Hieroglyphics is fully evidenced by the mound of unopened envelopes that lay next to Tajai’s feet. Sometime after the seeds of the Imperium were sewn, Tajai ran across a fan’s Internet site dedicated to the Hieroglyphics. It was created and maintained by 17-year-old Yameen Friedberg, a/k/a StinkE, an aspiring Web designer and devout Hiero fan from Philadelphia. Besides admiring its impressive design, the Hiero crew realized a Web site could also increase their presence with their fans. They partnered with StinkE, and hieroglyphics.com (www.hieroglyphics.com) was created.

The site supplies news on the artists of Hieroglyphics, the chance to participate in real-time chats, and provides enough information for any novice to feel like they were in the know. More importantly, the site provided a venue from which the crew could raise money through the sales of merchandise. T-shirts, gear, and special tapes, like the Domino’s Hiero Oldies tape, a collection of demo songs and unreleased cuts, are all available—just enough to feed the appetite of music-starved heads.

“Our goal right now is to get this [3rd Eye Vision] album out. All the money that we get from selling shirts and tapes all go towards funding this album, because we don’t have tons of money,” admits Domino. “The fans that support us are great. What can you say? They’re down with us, despite all the problems we ve had.”

“This is lunch money for tomorrow, boy,” exclaims Tajai, pulling out three five dollar bills from an international air-mail envelope. A pile of unopened envelopes sit by his feet, orders from the Web site. The majority that have come in so far are for Del’s “unreleased” Future Development album.

“Damn, this guy sent the order from Holland.” I point out to Tajai that the kid probably had to go through a lot to get American dollars, a sign of true dedication. “You’re right. Maybe I should send him a letter.”

That Tajai has the time to enter names and addresses into a database is commendable. The 22-year-old anthropology student is on spring break from Stanford University, where he is trying to focus his efforts on graduating in May.

“I have less time to create because before, everything was taken care of, he admits. “But now, I feel freer as a person. I feel like I’m working towards a goal, which is empowering. The goal is to build a foundation. Even if I don’t see hella money, I have the experience. Hieroglyphics will have some sort of franchise, a conduit to do other things.”

“School taught me how to look at the world beyond rap music. It also taught me how to look at the world from inside rap music. That’s basically anthropology.”

Tajai’s senior thesis is on the ethnography of the Bay Area Hip-Hop scene, and the paradox of how Hip-Hop exists as both a part of and a rebellion against American culture. How’s that for lyrical inspiration? I ask him how he thinks school has affected his rhyming.

“I think I’d be a lot more grandiloquent if I didn’t go. I think I’d try to sound more educated than I would actually be. Going to school helped me be more concise. Helped me edit my shit, and look at things critically. I learned a lot about language.”

“We’re a thinking man’s group,” Domino says, indicating that Tajai’s background is indicative of the type of Hip-Hop the Hieroglyphics make. “You really have to love words and vocabulary to really understand what some of Hiero is saying.”

The impact the Hieroglyphics made on Hip-Hop is not lost on them. They know exactly how they, along with other lyrically focused crews (i.e., Freestyle Fellowship), opened the doors for MCs to rhyme a certain way. It was not revolutionary, the way a Rakim or Kool Keith created a new rhyming paradigm, but just as effective.

“When we first came on the scene, we brought something new to the table,” A-Plus says, unapologetic. “Here’s new ways to rhyme, new ways to flow, new ways to land your syllables. Many people had done that in the past, we were just another one of them that happened to do it also.”

“This album we’re about to do is going to change the ways MCs flow again,” says Casual later, confirming what everyone in Hieroglyphics already believes. Sure it borders on conceit and arrogance, but that seems to be what motivates the individual artists. No disrespect, they say, but they’re simply some of the best MCs on the planet.

“If it ever comes down to some judgement day stuff, as far as there being a huge battle royal or some stuff, we’re going to leave with hella top spots,” boasts Tajai. “Almost all of them. You have to reserve the honorary ripper award for KRS. The lifetime achievement award.”

Del is finished with his video game, a Japanese game that needs a special adapter in order to be played on US machines. After ostensibly saving the president’s daughter from a band of terrorists, he’s enjoying the spoils of victory with a clove cigarette in the backyard. One clove turns into two turns into five turns into twelve. Sometime in between, Del grabs Opio’s new bottle of Hennessey and begins to drink it against everyone’s wishes.

He laughs when he’s reminded of Tajai’s KRS-One comment. Surprisingly, Del met KRS for the first time at the Gavin in February. (Someone in the house has been steadily feeding the tape deck with Boogie Down Productions and KRS-One albums all afternoon, so the respect in which they have for him is quite evident).

Del the Funky Homosapien is by far the most prolific of all the members of Hieroglyphics. “He’s got volumes of rhymes,” snickers Casual. “Books and books and books. Nobody can keep up.” Words that ring true, considering that Casual has some 50 songs in the pipe for his upcoming album (rumor has it he’s about to be signed to DreamWorks). Casual and Del share space on a song titled “Checkin’ Out the Rivalry,” another one of those “What if?” combinations that indelibly delivers. Del shares another song with Opio, “Oakland Blackouts,” arguably the strongest cut on the album and one that highlights exactly what it is that makes Del’s presence in the crew so necessary. Del’s low-end voice and knack for bending words and phrases around beats integrates his rhyming into the fabric of the song. The foundation he creates is perfect for a free-floating rapper like Opio, or a knife-tongued MC like Casual to get off.

Spiritually, though, Del is the backbone of the Hieroglyphics. He provides stability, a level, if not sometimes strange, head in the wake of success and adversity. When the controversial Hieroglyphics vs. Hobo Junction battle happened two years ago, Del was notably absent from the proceedings (“I was at home,” he says mildly). Not only did he not get caught up in the foolishness, but he was behind the scenes trying to squash it.

While the other members of Hiero carry themselves with bravado, Del is a self-imposed introvert. He is an elitist nerd that carries with him his own set of baggage. He is the kind of kid that in high school said “I hate all you motherfuckers,” and would go off to play Dungeons and Dragons all by himself.

But while everyone speaks of Del with the utmost respect, one can’t help but shake the feeling that they still look after him like a younger, more irreverent brother. His alcohol intake is hard to rival, and somewhat disturbing. It sends him on long, slurry-voiced diatribes, often provoking him to interrupt conversations with long ramblings about…I can’t exactly figure out what he’s talking about. At one point during our conversation, the mention of Special Ed instigates a word-for-word recital of three songs from Special Ed’s last album.

“Del is a true artist,” explains Domino. The only thing that seems to matter to Del are beats and rhymes. He spends the rest of his time playing video games and watching Japanese animation. He’s notorious for his use of acid and shrooms (and getting busted for hash), though it is alcohol that is his poison of choice now. Somehow, he—in Hendrix-like fashion—squandered all the money he made from Elektra, a lucrative contract that was surely the major reason he was let go. (He got a job with a local record store called Leopold’s. It was a tantalizing bit of info that had members from the cult of Hiero come from as far away as New York to check its validity and gawk as if he were a part of the circus).

Del spent three months learning Japanese (prompted by his loyalty to Japanese video games and animation), and has spent the last six months teaching himself. And, if it weren’t for his girlfriend, Del may not have a place to sleep. After digesting all this, and his three albums’ worth of music, I realize Del is not only a living artistic genius, he’s also Jean-Michel Basquiat.

“Niggas know I’m not the normal nigga on the block,” he says between sips of the Hen. “Weird Del, crazy Del, I’ve heard it all. It might add a little mystique to my name or whatever, but niggas don’t really know what’s going on. I’m just a normal nigga. Niggas be givin me major love when they see me, so that’s tight. That makes me want to go back to the lab.”

The background soundtrack changes. The UMC’s “One to Grow On” replaces KRS-One, and the setting is punctuated with a sense of nostalgia. The contrast between Hip-Hop back then (only a few years ago) is something Del feels everyday. His stream of consciousness continues. “Rap is so weak to me now, I don’t even give a fuck about that shit. I call my shit ‘mind music.’ It’s derived from Hip-Hop, because that’s my life. But you have to use your mind to get into it, like the three eyes on the Hieroglyphics symbol.

“For most niggas, it’s a passive thing, like listening to MC Hammer while washing dishes or something—I saw my mom doing that. It ain’t like you spend your time sitting down listening to an album. Sometimes I’ll turn an album on and just sit and listen to it. A lot of motherfuckers do that, but the majority of niggas don’t. Majority of motherfuckers will buy a record because you’re supposed to have it. You ain’t cool if you don’t have it.”

The afternoon has turned to evening, and for one brief moment, Del, Domino, Opio and Tajai are all outside in conversation. Two skater kids have come over to watch Souls videos and hang out with Del. Tajai doesn’t seem to know who they are, but he welcomes them in nonetheless. (No doubt they, too, are part of the Hieroglyphics cult). Everyone’s talking about Hip-Hop. Not sales or marketing or radio promotions or whatever, but the music. Domino’s favorite song is “Oakland Blackouts,” Opio favors “The Who.”

It becomes obvious that nobody will buy Third Eye Vision because they feel they have to have it. The Hieroglyphics make records that make people want to have it. They make records that provoke. Provoke people to seek out B-sides like “Eye Examination,” and “Undisputed Champs.” Provoke fans to scour Web pages and newsgroups to find out what’s up with the Hiero crew. And provoke kids to dig up obscure demo songs and dub tapes from locations as remote and unassuming as Nashville and Boise.

Domino hands me a copy of Domino Oldies Volume 1 as I make my exit from Hieroglyphics Central. “It’s got ‘Cab Fare’ on there, in case you don’t have it.”

“That’s OK,” I say with a smirk. “I already got it.”

Reproduced on Hieroglyphics.org for educational purposes.